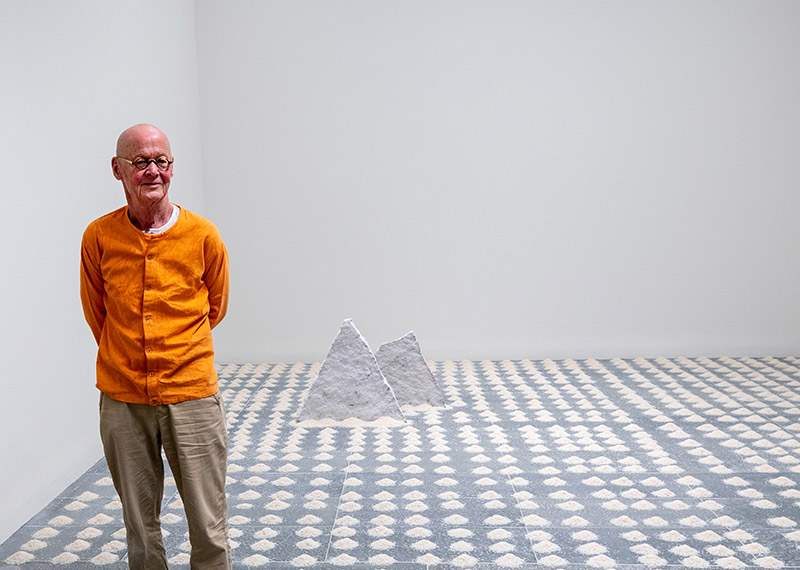

At the end of this March afternoon, a white stele was erected in the oval room ofWater lilies, and a small audience holds its breath as Wolfgang Laib approaches. The German artist is the twelfth guest of the Contemporary Counterpoints program, launched five years ago by the Musée de l'Orangerie. But he is the first to create an in situ installation in dialogue with Claude Monet's panoramic frieze. Dressed all in white, hairless head, glasses with thin round frames on his nose, Laib unscrews the lid of a transparent jar which reveals its intense yellow contents. He gently dips a spatula inside and places a spoonful of granular powder on the stele, then another, slowly, and another. A tiny golden embankment is gradually forming. After a few minutes, the artist closes his jar, takes a step aside, the audience applauds. The ceremony is over. This is not the first time that Wolfgang Laib, known worldwide for his work related to nature, has performed this silent ritual. From the Beyeler Foundation in Basel to Moma in New York, he has, on many occasions, spread in museums grains of hazel, pine or dandelion stamens (previously collected around his studio, in the middle of fields, on the edge of the village in southern Germany where he spends half the year). Along with milk, rice, and beeswax, pollen has been one of his favorite materials for more than forty years, from which he creates his installations: alcove of fragrant wax, immense solar monochromes made of drawn pollen on the ground, alignments of small pyramidal piles of rice… The shapes are geometric – rectangles, squares, triangles – or they borrow from the vocabulary of architecture – house, tower, staircase, ziggurat (Mesopotamian religious building). The repetition of gestures and rigorous lines is at the heart of his work, which has persisted for forty years, taking on a different meaning over time. He likes to say that he doesn't create but “shows” the beauty present in nature. “Pollen is the origin of life,” he simply remarks. It is not a pigment to make a painting. »

a childhood of art and travel

The meaning of his work lies, as he himself affirms, ” beyond “ of representation. “Nature and beauty are the same thing. I can't create anything as beautiful as nature”, he chants like a mantra. Like a legend, his biographical story also invariably unfolds the same initiation story. That of a child who grew up in a German family loving art and travel, and of a long-term friendship with Jacob Bräckle, a landscape painter from Biberach steeped in Chinese philosophy. The Laibs went on vacation to Europe, visiting the great medieval cities, the Romanesque churches and, on several occasions, the city of Assisi, linked to the life of Saint Francis, a figure who marked the thinking of young Wolfgang. In the mid-1960s, they went to Turkey to visit the tomb of the Sufi poet Djalal ad-Din Rumi. The absence of furniture in rustic Turkish homes would have inspired the Laibs to design their house minimally. Built in glass, in the middle of meadows and woods, it already constitutes a radical artistic experience. Soon Wolfgang Laib and his parents will discover Asia and more particularly India, where the artist will later set up his studio and where he now spends several months of the year. A graduate of the University of Tübingen, Wolfgang Laib could have worked as a doctor, like his father. He hesitated. To finally choose to heal the ills of men and society differently, thanks to art. In 1975, he created the first of hisMilkstones (milk stone) – rectangular white marble sculptures in which the rock is sanded to create a slight depression, which the artist fills with milk. At the Orangerie Museum, the small pile of pollen symbolically erected will not remain for more than a few hours in the middle of “the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism”, where no other work is tolerated. But in the introduction room Water liliesWolfgang Laib designed an identical pyramid of pollen placed under a glass window: A mountain that cannot be climbed. For Monet.

an economy of means

This tribute to the painter is part of a reflection begun recently. “Since 2019 and his exhibition “Without Time, Without Place, Without Body”, in Florence, Wolfgang Laib has begun a dialogue with works from the past, such as at the San Marco convent with the paintings of Fra Angelico, or at the Chapel of the Magi at the Medici Riccardi Palace, reports Sophie Eloy, collection assistant, in charge of Contemporary Counterpoints at the Musée de l'Orangerie. It thus establishes a relationship based on subtle perceptions between visible art and the invisible spirit. » For some time now, we have also seen him more alongside his wife, Carolyn Laib, a former curator specializing in Asian arts whom he met in New York in the early 1980s. Winner of the prestigious Praemium Imperial in 2014, Wolfgang Laib has benefited from a traveling retrospective in the United States from the early 2000s. His work is also very popular in France. In 1992, he created a large pollen square in the Pompidou Center forum, “rapidly dispersed by the ventilation system and passing pigeons”, remembers an art critic. The protocol has not always been infallible… But today it is more contemporary than ever. The economy of means of his installations, which often require little more than a few jars, a bag of rice, and infinite patience, appeals to museums. No transport costs for works or exorbitant insurance policies, little handling, Wolfgang Laib is the guest that institutions dream of. As for his words, which invite us to reflect on the beauty and fragility of nature through an essential, elementary encounter, it resonates more than ever with current events. In a context of climate emergency, degradation of our environment and extinction of species, Wolfgang Laib's work has never seemed more relevant. In the basement of the Orangerie Museum, the installation Rice field thus includes two triangular granite steles “covered with sacred Indian ashes”, reflection on the cycle of life and death. From the beginning, the artist has claimed a spiritual dimension. In 2017, in the Parisian space of his gallery, Thaddaeus Ropac, he presented six ovoid black granite sculptures of different sizes in the middle of a room whose walls are covered with 28 almost invisible drawings on a white background. The bringing together of these full, massive forms and these diaphanous graphic works echoes one of his very first installations. And generates, he assures, “incredible energy”.

repetition of gestures

Underlining the timeless and universal character of his art, Wolfgang Laib readily says he is very happy to see how much he can “giving to so many people around the world”. The impassive seriousness of the words clashes with the gentleness of the voice which states it. Beneath his appearance as a Zen monk, the artist reveals the impassive assurance of a guru. However, it is to favor doubt that he chose the path of art. “People think I'm a Buddhist, but that's not the case,” he said in an interview. I chose not to enter a monastery but to become an artist, that is to say, not to know where I was going. »Without ever deviating from his path. Tirelessly, from exhibition to performance, the artist recreates the same pieces, deploys the same materials, immutably reiterates the same gestures. “These, like the renewal of the seasons, propose a reformulation of the eternal essence of nature and life, which is never strictly quite the same”, already wrote Margit Rowell, then curator at the Center Pompidou, more than thirty years ago. Wolfgang Laib does not vary. And that's all its strength.

1950

Born in Metzingen, Germany

1968

Study medicine in Tübingen

1975

Series of “Milkstones,” Or “milk stones”

1982

Represents Germany at the Venice Biennale

2008

Exhibition at the Grenoble Museum

2013

Exhibition at Moma in New York

2015

Winner of the Praemium Imperiale in Tokyo