Paris,

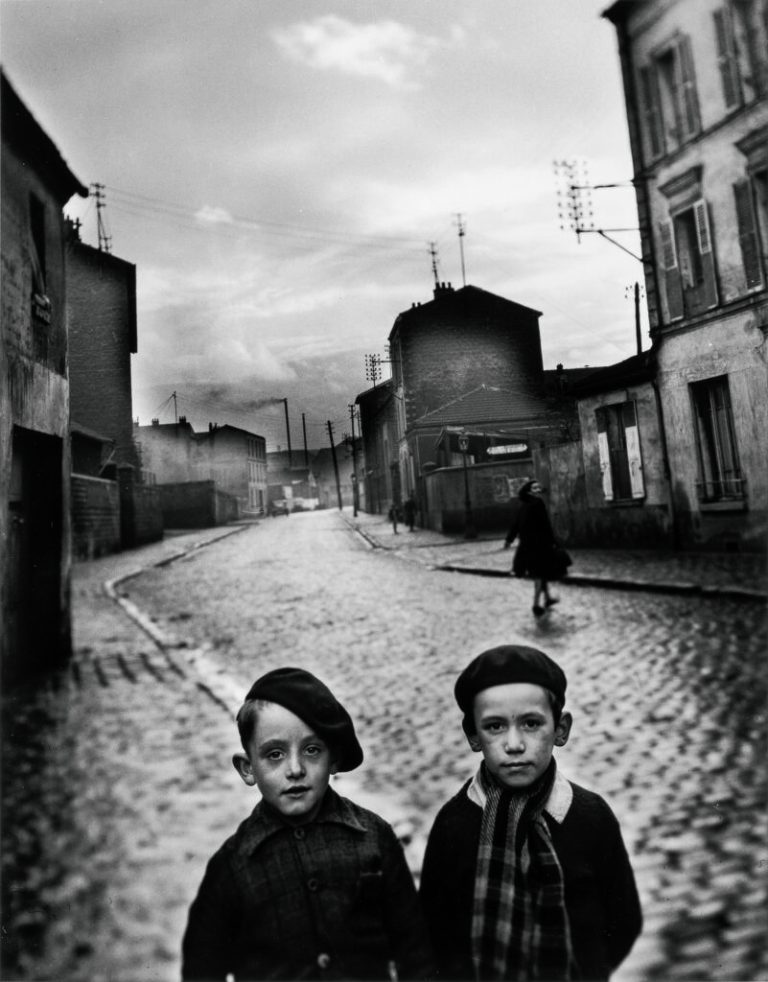

120 years ago, the then young Romanian artist crossed Europe on foot to settle in Paris. There, in a period of full cultural effervescence in the French capital, Constantin Brancusi would lay the foundations of a new way of sculpting, a language based on direct carving and simple forms that soon aroused the interest of many: artists and admirers came en masse to the workshop where he lived and worked, in Impasse Ronsin (15th arrondissement), which he himself conceived as another work of art and which he would donate to the French State as a whole in 1957.

Precisely the pieces bequeathed to France by this author constitute the matrix of the large exhibition that the Center Pompidou now dedicates to him, complementing them with loans from international institutions: his sources and major themes are reviewed and it is also emphasized that his work went beyond the sculpture, delving into photography, drawing and even cinema. Brancusi was an artist deeply attached to his time, who encouraged the public not to revere his pieces, but to love them and play with them. The last retrospective that was given to him in the neighboring country also took place in this museum, in 1995, and on the occasion of his renovation works and the necessary complete transfer of the Atelier Brancusi – to the rooms of the Pompidou, after his initial passage through the Palais de Tokyo – it was considered appropriate to compare the plasters it guarded with stone or bronze originals from the Tate Modern, the MoMA, the Art Institute of Chicago or the Romanian National Museum.

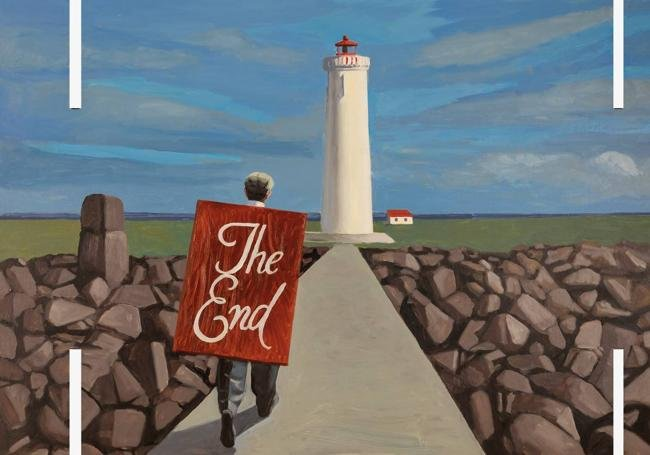

A partial reconstruction of his workshop, invaded by clarity and white tones, will allow us to get closer to the material and processual dimension of his creation (materials, tools, techniques); It should be taken into account that almost every piece in it had come from the artist's hand: from the limestone fireplace to the wooden stools or the plaster table that he used both as furniture and as a base for his creations. After World War II he practically stopped sculpting and moved, but in his atelier he continued grouping and recombining works and, to maintain the unity of the group, when he sold one he replaced it with its version in plaster or bronze.

The center of the exhibition reviews his sources (Auguste Rodin, Paul Gauguin, Romanian vernacular architecture, African, Cycladic, Asian art…), while delving into the aesthetic keys of his compositions, such as his love for the fragment, seriality or the work of sublimation of forms. To contextualize Brancusi's life and work, abundant documentation has also been gathered (letters, press articles, diaries, records), which he kept meticulously and which will give an account of his friendship with creators of interests as diverse as Duchamp, Léger or Modigliani. . This archive was acquired by the Pompidou in 2001, is kept in the Kandinsky Library and is a gold mine of information to delve into his life, relationships and tastes; also to understand the fascination that he exerted on his contemporaries. Various photographs will show us cutting, sawing or carving.

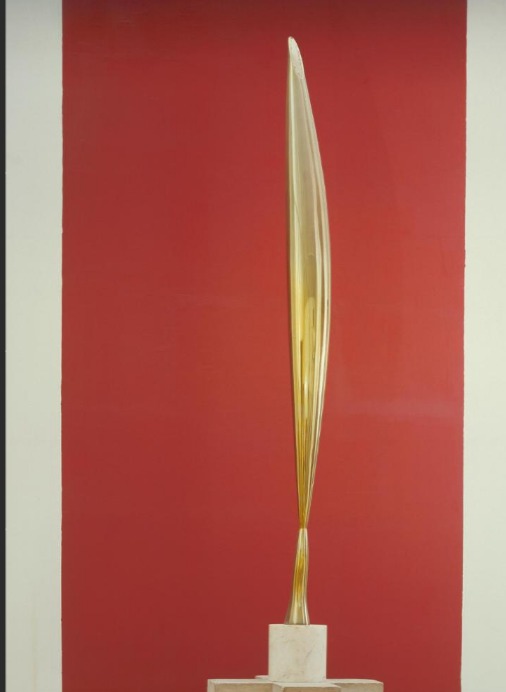

The tour has been organized thematically, around its fundamental series and in half a dozen sections dedicated to the ambiguity of form, the portrait, the relationship with space, the role of bases or supports, the games of movements and reflections. , the representation of animals and their treatment of monumentality; of this last section are part The kiss and The endless columnwhich was installed in Edward Steichen's garden in Voulangis and proposes, starting from a modest wooden base, the repetition of the same module in vertical ascension, in reference to the funerary pillars of southern Romania.

When he arrived in France, the artist already had academic training; he was 28 years old. Rodin soon appreciated his talent and in 1907 offered him a job as an assistant; He remained with him for a brief but decisive time (Brancusi justified his departure by saying that nothing grows in the shadow of a large tree). Three works dated between that year and 1908 (The kiss, The wisdom of the earth and The sentence) They make clear their desire to find their own path, which as we said would not be linked to modeling but to direct carving. He also abandoned the meticulous observation of models to reinvent the figures from his memory.

Basically, we can see in his pieces a kind of melting pot of the art that he could contemplate then: the ancient or non-European works of the Louvre or the Musée Guimet, the painting attached to the primal of Gauguin or the cubist investigations of André Derain. His series based on the motif of a child's head anticipates his later path of fragmentation and simplification of forms intended to express, in his words, the essence of things.

However, paradoxically, this simplification and the elimination of details becomes, in his case, a source of antiquity. We see it in her female torsos, a motif that she began to cultivate in 1909: in her Woman looking in a mirrora piece that we can still consider classic, we only clearly identify the curve that unites the rounded shape of the head with the chest, and even more ambivalent is the famous Princesse, possible representation of both a feminine ideal and a phallus. This lack of definition caused scandal and the rejection of this sculpture at the Salon des Independants in 1920; Basically, Brancusi was playing with metamorphoses and with the fusion of the masculine and the feminine in the same work, as we also see in The kiss. His Young man torso, title aside, also presents an uncertain genre: its alteration of the symbolic order of the division between the sexes could be related to the rebellious spirit that simultaneously drove the Dadaists; In addition to Duchamp, Man Ray and Tristán Tzara were among his friends.

It is difficult to understand, at this point of moving away from the visible to reach the essential, the importance of the portrait in Brancusi's production, but it was there. Although the titles of these sculptures retain the names of those who never explicitly inspired them (Margit Pogany, Baroness Frachon, Eileen Lane, Nancy Cunard, Agnes Meyer…), their effigies seem to mix and, again, merge, in a stylized, oval face and smooth. They are not entirely the same nor entirely different; Each one is distinguished by basic features: almond eyes, bun, curls…

By working from memory, we can reflect from these works on the multiple difficulties of representing a faithful reality or an idea. In the drawings, for his part, he used to break down the figures into reliefs and silhouettes.

Another recurring motif in Brancusi was that of flight: more than thirty variants, in plaster, bronze and marble, he dedicated to birds over thirty years. He started in 1910, with Teachers with rounded bodies, elongated necks and open beaks that refer to a popular bird in Romanian tales; Already in his twenties, he slimmed down his shapes and stretched them vertically in the series Oiseaux dans l'espace. It is very likely that this matter of flight symbolized for the artist man's dream of escaping his earthly condition to elevate himself spiritually; Although the project remained in a draft, the Maharaja of Indore commissioned two for an Indian temple in 1930, and the subtitle of another that he exhibited in New York in 1933 was Project d'Oiseau that, enlarges, employs the sky (Bird project that, enlarged, will fill the sky).

They were not the only animals he sculpted: in the thirties and forties, and using oblique and horizontal shapes, he created both roosters and swans and aquatic specimens (fish, seals, turtles…), in many materials and formats and seeking a sensation of dynamism. .

It is important to talk about the textures of Brancusi's works: even in the photographs from his studio, we can appreciate the contrast between the pieces with highly polished surfaces, in which all traces of the sculptor's gesture disappear, and the raw or barely treated ones. This play of materials is as tactile as it is visual, as he himself emphasized when choosing titles such as Sculpture for birds (Sculpture for the blind). Another aspect to which he paid a lot of attention was its bases, sometimes composed of overlapping elements of simple geometric shapes; These supports give rise to a dynamic ascending rhythm and combinatorial games, in no case are they conventional bases. We can even contemplate them as autonomous sculptures, proof of his challenge to previous hierarchies.

Brancusi

POMPIDOU CENTER

Place Georges-Pompidou

Paris

From March 27 to July 1, 2024