Madrid,

The MAPFRE Foundation, one of the institutions that has been most committed to discovering photographers who are almost unknown in Spain but relevant for the universality of their work, coincides with two exhibitions dedicated to authors who thoroughly addressed the validity and prejudices of racism in their work, one in the South African context (David Goldblatt) and another in the American context (Consuelo Kanaga). In addition to their social commitment and their attention to injustices, both are also united, as Nadia Arroyo, director of the Culture Area of that institution, pointed out today, an aesthetic far from spectacularity.

After his recent visit to Barcelona, this retrospective of Kanaga arrives at Recoletos, whose career had not until now been thoroughly reviewed either in our country or in Europe, despite the fact that he did achieve recognition during his lifetime. His career was marked by a gaze directed at the suffering other and his care for the expressiveness of faces, body language and the use of direct natural light and marked shadows; He was very aware, as early as the one he lived in, of the artistic value of photography and his commitment was twofold: against racial discrimination and for artistic modernity in his country.

Born in 1894 in Astoria (Oregon), she dedicated a good part of her production to women and the African-American population, concerns that she probably began to cultivate as a result of her dedication to journalism: the daughter of a lawyer and writer, she helped her parents with homework. editing and writing before joining, in 1915, the San Francisco Chronicle –means that made her, a few years later, a staff photographer, the first woman- and then to Daily News from the same city. She would delve into those moments at the California Camera Club, where she was able to discover her first darkroom and Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston and Dorothea Lange, with whom she shared a social perspective and friendship: the first was a true reference for her; she said she was the greatest woman I had ever known, generous, humane and brave. The discovery of the magazine Camera Work de Stieglitz also allowed him to discover artistic photography.

Another group with which he was associated was f/64, and in his first exhibition, at the MH de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, he also participated before documenting different workers' struggles, arriving in New York and joining the Photo League. Steichen, over time, would become one of its greatest supporters and would include it in the exhibition “The Family of Man” in 1955, at the MoMA, which would be followed by other, now individual, exhibitions at the Lerner-Heller Gallery, the Brooklyn Museum (which gave him a small but important retrospective and to which he donated his archive of five hundred images) and Wave Hill, Riverdale. After her death in 1978, she was part of the collective “Recollections: Ten Women of Photography” at the International Center of Photography in New York, and the Brooklyn Museum dedicated another anthology to her.

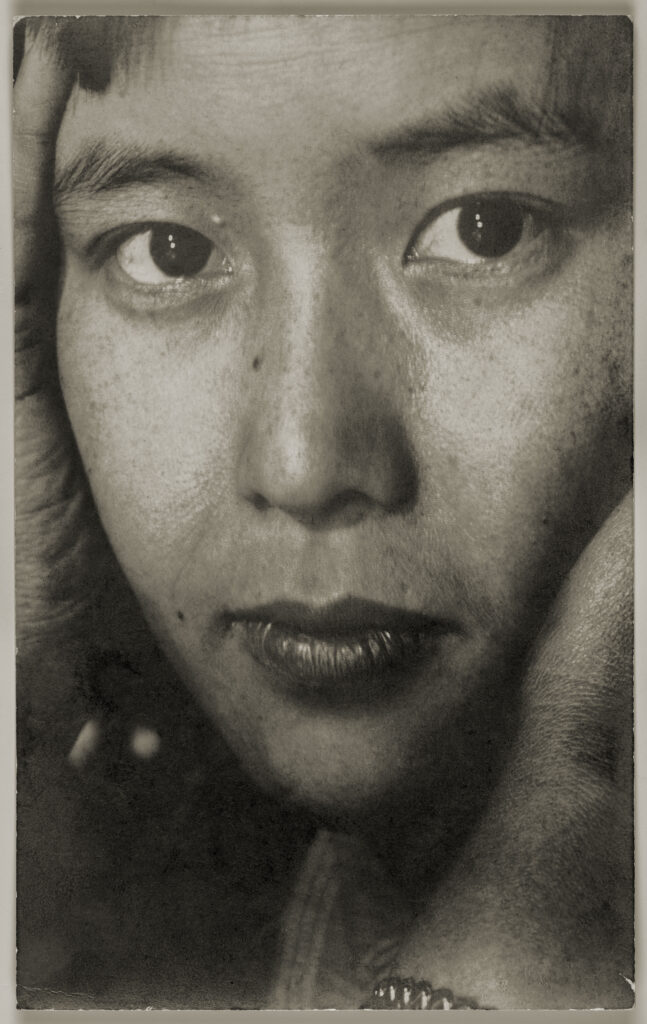

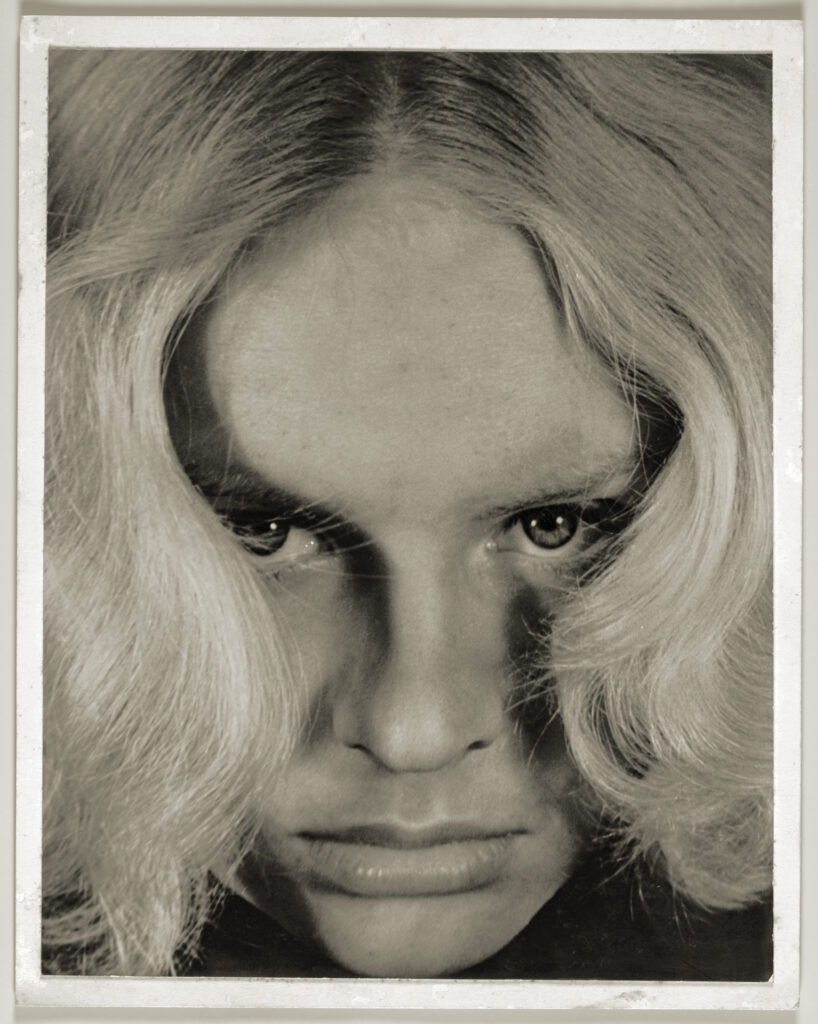

The one that we can visit until August at the MAPFRE Foundation, organized together with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and curated by Drew Sawyer, focuses on the imprint on his career of his first work as a photojournalist (he was taking images to illustrate his reports as he was able to learn the trade, encouraged by the director of the Chronicle) and in their testimonies of the cultural movement called New Black, which was developed in the twenties and thirties and marked a flowering of black artists and writers (Sargent Johnson, Langston Hughes, William Edmondson… whom the complimented texts on the posters invite us to get to know), but it also appealed to whites , demanding your support in defense of equality; Kanaga responded to that call. We will also contemplate the portraits that she gave to her extensive and influential circle of female friends, many of them photographers whom he inspired or by whom she allowed herself to be inspired; This is the case of the aforementioned Imogen Cunningham and Dorothea Lange, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, traveling companion in Europe and Africa, Alma Lavenson, Tina Modotti and Eiko Yamazawa, her assistant and later a pioneer of photographic modernity in Japan.

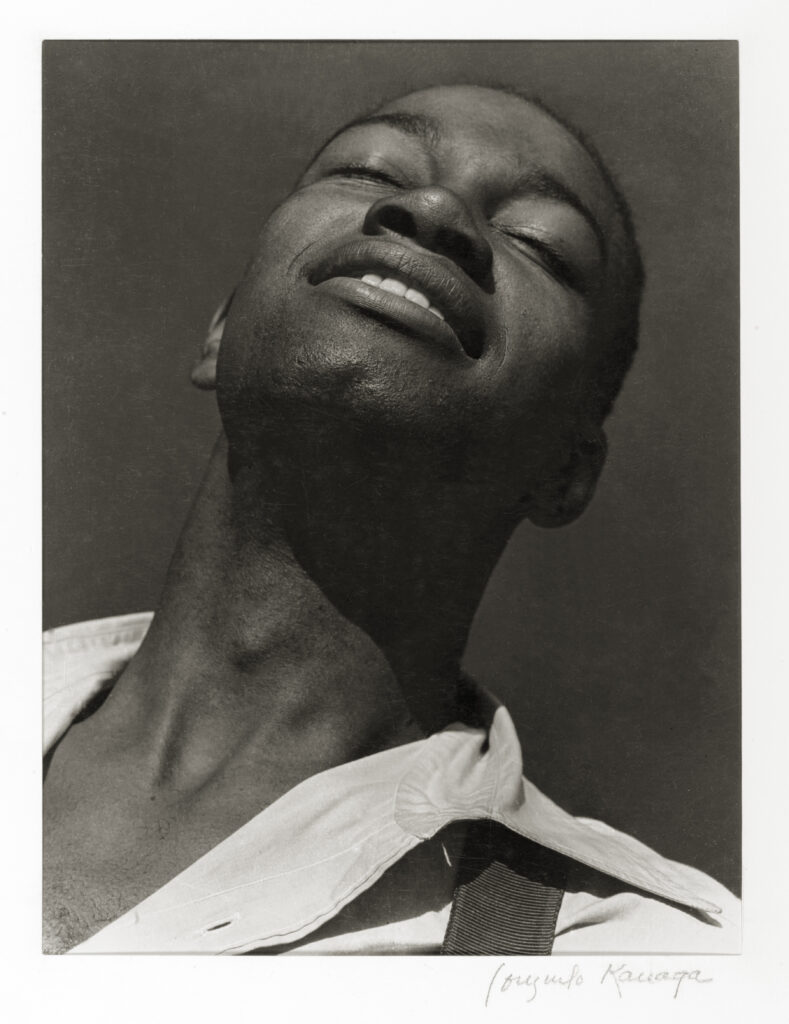

In the same way that he privileged his relationship with them over self-promotion, the center of his work was human affairs: he focused on poverty and the living conditions of the marginalized, on those who were victims of racism or inequality, without leaving aside that of investigating the formal options of photography as art. His compositions dedicated to African-American citizens have been the most widespread and Sawyer has explained that the purpose of this project is to contextualize them historically and politically and to emphasize his departure from clichés, in addition to his desire for style; He shared the idea that every photo is a reflection of both the subject captured and the photographer's feelings towards him, and stated: When you take a photograph, it is largely an image of yourself. That's what's important. Most people try to be flashy to get attention. I think the point is not to capture attention, but to capture the spirit.

It is difficult to elucidate the reasons why she has been left in the shadows so far compared to her aforementioned colleagues, but they would surely have to do with her full-time jobs, which forced her to pick up the camera especially on weekends; with her dedication to her partners, for whom she put aside her career several times; or by her discovery of her beauty on grounds where only the complaint was expected.

When you take a photograph, it is largely an image of yourself.

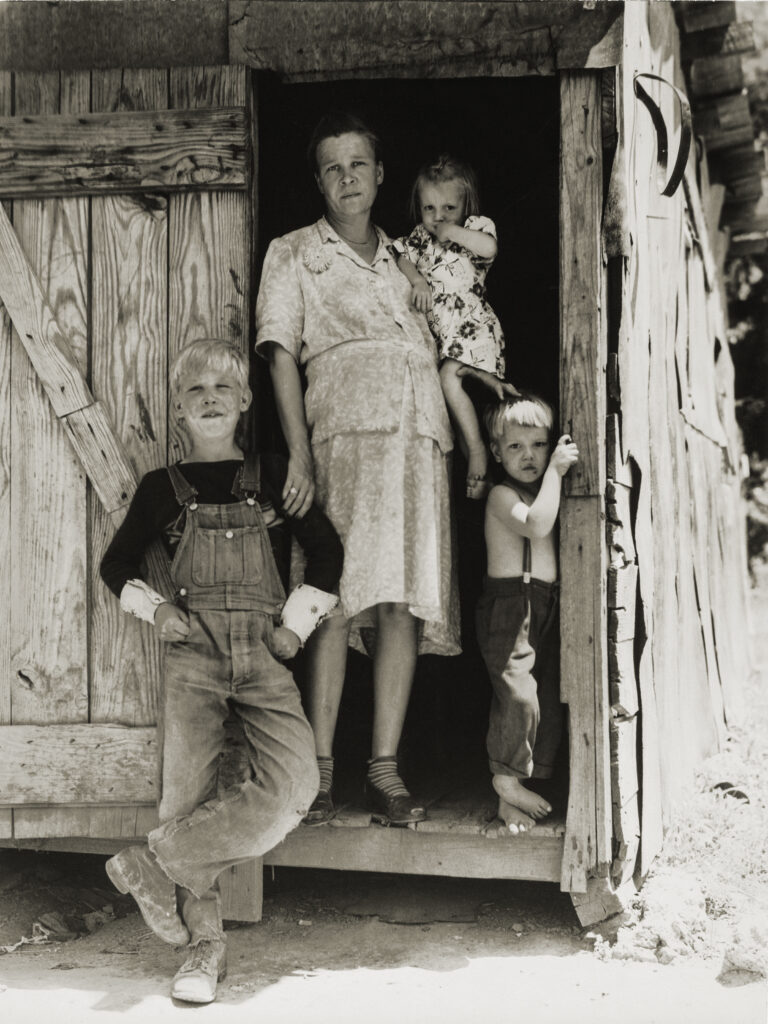

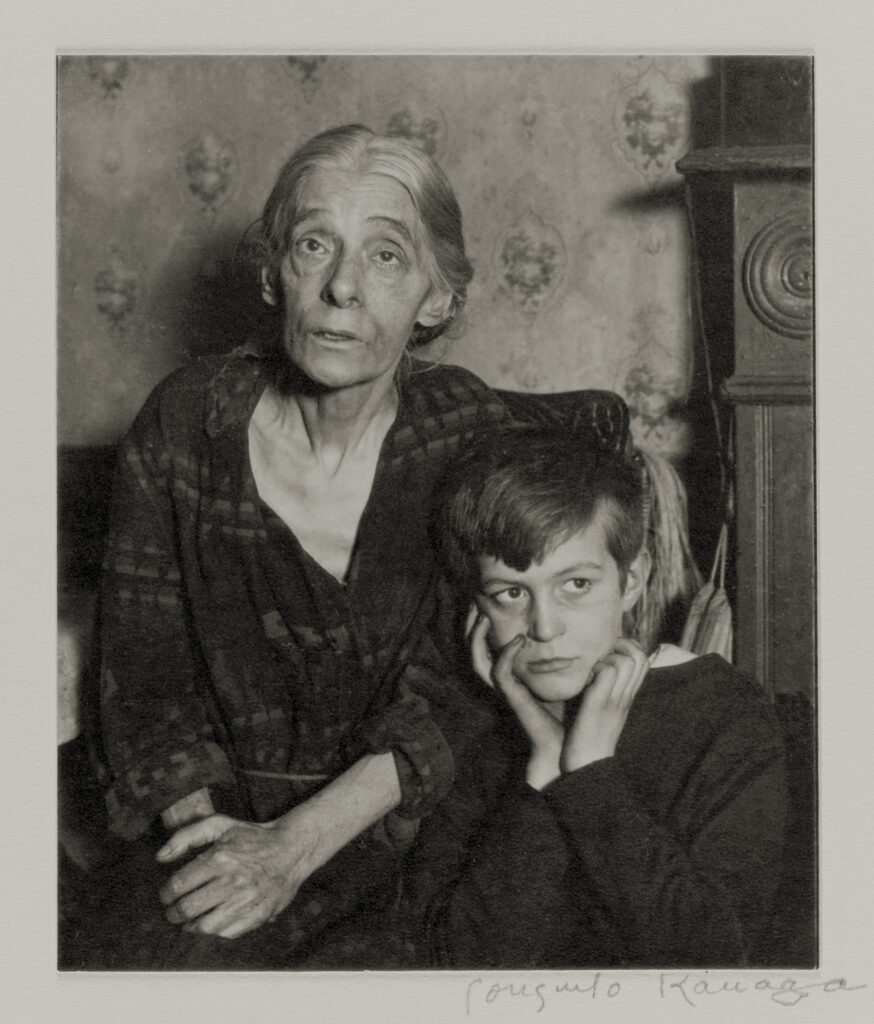

We will begin by considering a selection of the works he carried out as a photojournalist, first, as we said, in San Francisco and then in Denver and New York. These are urban scenes that usually present us with portraits of this inequality, among them that of The Widow Watson (1922-1924) for the New York Journal-American: captures a woman sick with tuberculosis with her son, but accentuating the humanity in their faces more than their situation of poverty, that is, what they have in common with every viewer. This, and other similar images of mothers with their children, circulated widely and would have a lot to do with Lange's view of her migrant mothermore than a decade after this work.

Among his sources of influence at that time was Arnold Genthe, author of always urban street views; He delved, in any case, into the value of the photo as a means of observation and into the approach of direct photography that Sadakichi Hartmann spread, far from the dominant pictorialism at the turn of the century.

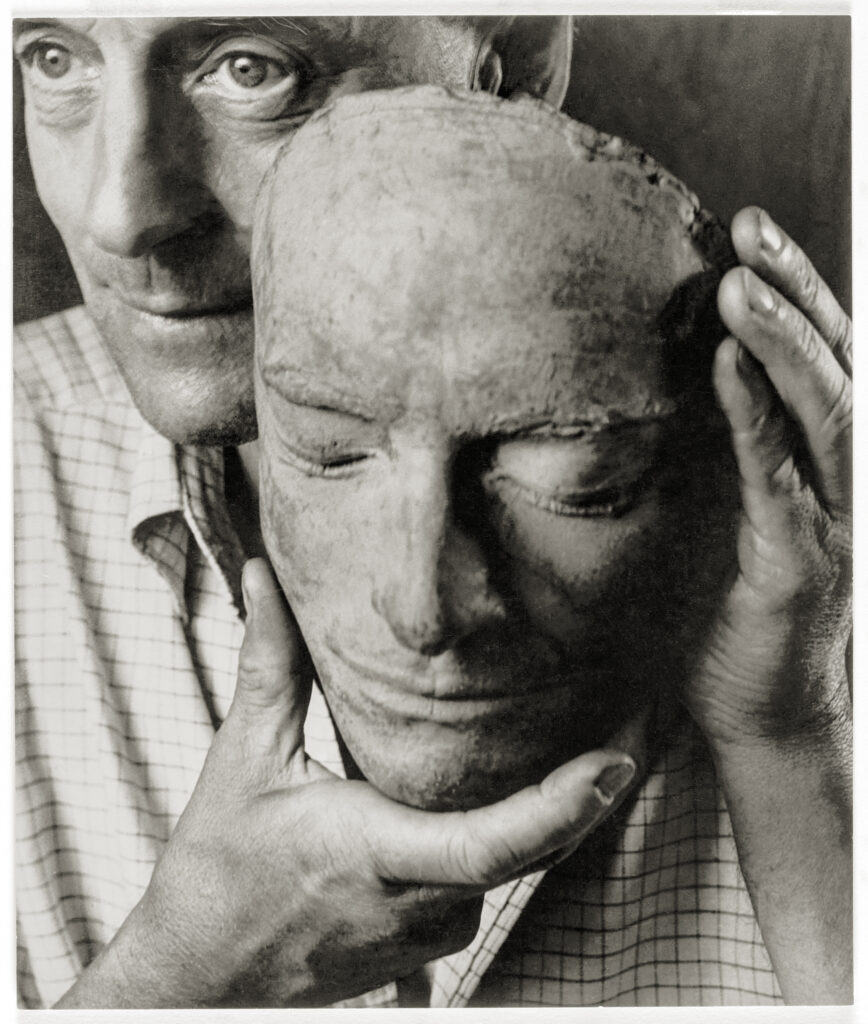

In parallel to these works, and also in both San Francisco and New York, Kanaga made commissioned portraits that allowed him to obtain additional profits and, therefore, greater freedom: he opened his own studio in the early twenties and this work made it possible for him to support himself. , to herself and her husbands, henceforth. Her clients were, above all, wealthy people and friends located in the avant-garde environment, and in these images she allowed herself to experiment with poses, lighting, cuts and prints to achieve the desired expressiveness; She used overexposure and underexposure, manipulating times, and she achieved theatrical effects by accentuating lights and shadows and playing with her hands. To highlight her features, she also turned prints with metals and added pencil or graphite. Although the images taken of her as a photojournalist are not always preserved, negatives and copies of her have reached us of this genre.

We advance before that Dahl-Wolfe was his traveling companion in Europe and Africa; That journey was made in 1927-1928, with the patronage of Albert M. Bender, and took him to France, Germany, Italy, Hungary and Tunisia, where he visited museums, monuments and churches and looked for some learning opportunities in what he had to do. see with photographic techniques. From that period, the series of images that he dedicated to the streets and people of Cairuán (Tunisia) stands out, bathed in sunlight that seems to connect them with nature and spirituality and captured in the closeness of their faces, which again makes them brings closer to those who contemplate; and those that she provided to the expatriate artists who were then residing in that country. He began in Africa to become aware of racism, as she wrote to Bender: I'm sick of seeing men and women of color mistreated by stupid white people..

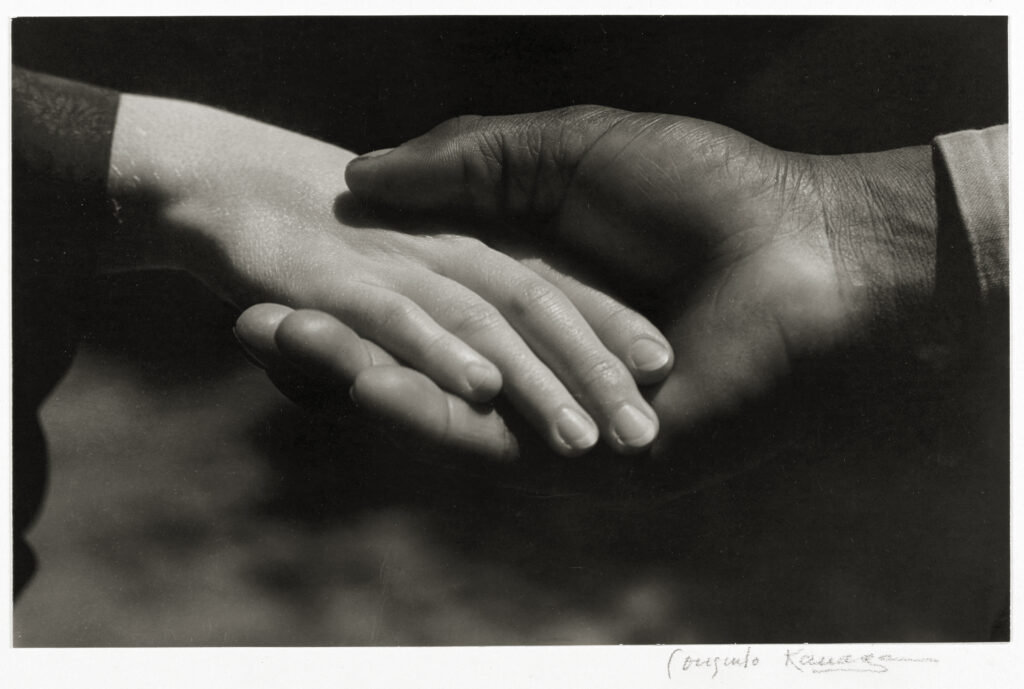

Upon his return to the United States, Kanaga would shape a personal model of American scenes: he celebrated ordinary people and local particularities, focusing above all on the neglected, from the architectures and objects that used to go unnoticed by the workers of common trades, often African-Americans. In parallel, and within the framework of the aforementioned movement New Blackportrayed those artists and intellectuals of color in images who came to celebrate their identity in the face of attacks and racial terror that would extend for a few more decades. Hands (1930), where she joins a black and a white photo, is the first preserved photo of this author that clearly reflects her anti-racist ideas and was included in an exhibition at the Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco in 1932, “A Showing of Hands.”

The labor movement was another of the thematic poles of her compositions, especially after the harsh working conditions that came with the crash of '29: from 1935 and in New York, she photographed for left-wing publications and, involved in the Photo League, defended the union of workers regardless of race and sex. Among the artists who, at that same time in the thirties and forties, passed through their lens to be portrayed included Alfred Stieglitz, W. Eugene Smith, Milton Avery, Mark Rothko and the designer Wharton Esherick; We will see them at the exhibition.

In the fifties and sixties Kanaga traveled again, but through the south of his country: he continued to photograph African-American children and workers, some of them day laborers in swampy areas recovered for agriculture (the mucklands); also the Peace and Freedom March of 1964. In addition, he photographed from an abstract approach the natural environment of his new rural house, north of New York, and the pond in his garden; These last snapshots could also be seen at the MoMA, in the collective “In and Out of Focus: A Survey of Today's Photography”.

Aside from the purpose of the MAPFRE Foundation to promote the production of little-known photographers on this side of the ocean, it is difficult not to relate Kanaga's images to those of another American author, also trained in San Francisco, who only two years ago passed through the rooms of KBr, its Barcelona space: Carrie Mae Weems, attentive to the black powercommitted to various anti-racist movements and non-violence.

“Consuelo Kanaga. Catch the spirit

MAPFRE FOUNDATION. RECOLETOS ROOM

Paseo de Recoletos, 23

Madrid

From May 30 to August 25, 2024